Rotifers

** Overview of Phylum Rotifera, Examples and Classification

Overview

Also referred to as "wheel animals/wheel-bearer", Rotifers are tiny, free-living, planktonic pseudocoelomates that make up the phylum Rotifera. While certain species can survive a given range of salinity, the majority of species can be found in freshwater environments worldwide.

As the name suggests (wheel animals/wheel-bearer), Rotifers are characterized by a ciliated corona located at the anterior end (head part of the organism). Currently, about 2000 species of the phylum have been identified.

Examples of Rotifers include:

- Brachionus quadridentatus

- Colurella adriatica

- Habrotrocha angusticollis

- Cephalodella gibba

- Brachionus urceolaris

- Lepadellaacuminata

Classification of Rotifers (Phylum Rotifera)

· Kingdom: Animalia/Metazoa - Kingdom Animalia consists of heterotrophic, multicellular, eukaryotic organisms

· Subkingdom: Eumetazoa - Eumetazoa is a large clade consisting of major animal groups with the exception of phylum Porifera. Members of this group are characterized by tissues that are organized into germ layers and neurons.

· Clade: Gnathifera - A large group that consists of small and bilaterally symmetrical animals. The majority of these organisms can be found in aquatic environments and are characterized by a complex jaw apparatus located at the anterior end of the organisms.

· Phylum: Rotifera - Tiny, free-living planktonic pseudocoelomates commonly referred to as Rotifers.

The phylum is further divided into the following classes:

- Class Pararotatoria

- Class Eurotatoria

Characteristics of Phylum Rotifera (Rotifers)

Morphology

Main Body Part

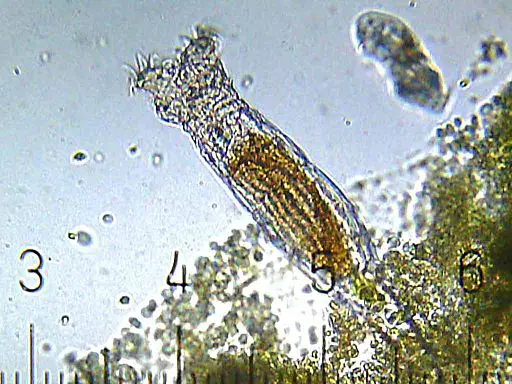

Generally, Rotifers are tiny animals that range between 0.1 to 0.5 mm in length. However, some species have been shown to grow up to 2mm in length. Depending on the species, they may appear saccate or cylindrical in shape with some of the species presenting a worm-like appearance (e.g. Rotaria).

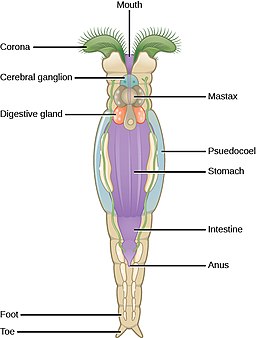

Their bodies consist of several main parts that include:

- Head - referred to as corona

- Neck - present in some forms

- Body

- Foot - Present in some forms

* While the body of Rotifers consist of several parts, it's worth noting that they are not segmented.

* The joint-like creases in Rotifers prevent the bodies of these organisms from collapsing telescopically.

Apart from the differences in body shape, differences can also be identified in the size and shape of the different body parts. In some of the species, for instance, the foot and neck regions may be significantly prominent but absent on others.

For species that posses the foot structure, it may have several toes (between 2 and 4 depending on the organism). Apart from the toes, these structures (foot) may have in place pedal glands with ducts extending towards the toes. Here, the glands serve to secrete adhesives that allow the organism to remain attached to given surfaces temporarily.

In some of the species (e.g. in sessile Rotifers) a cement-like substance is released by juvenile forms that allow the organisms to be tightly attached to substrates. These organisms may be attached to substratum until they mature (adults). In the event that they become detached, they cannot reattach again.

Parasitic Rotifers have been shown to possess a body wall that consists of a filament layer. In some of these species, this layer is reinforced by a thick intracytoplasmic lamina and is referred to as loricate. While those with a thin intracytoplasmic lamina are referred to as illoricate.

Corona

Corona is a defining characteristic of Rotifera species. However, significant variation of this structure has been identified between members of different species. Given that these differences have also been identified within a given genus, the general shape of corona is not solely used for identifying different Rotifer species.

For a good number of species, the corona consists of two ciliated rings (trochus and cingulum). Using these structures, water currents are created thereby contributing to locomotion. The currents created also draw in prey during feeding.

In some of the species (e.g. members the family Collothecidae) a ciliated corona is absent. Rather, they have long setae surrounding the rim of a funnel-shaped structure known as infundibulum. For organisms that possess cilia, it is sparsely located around this structure. Like ciliated corona, the structure serves to capture prey.

Depending on the organism, some of the other structures that may be present on the corona include:

- Sensory antennae

- Palps

- Cirri

- Vestibulum

Digestive System

The digestive system of Rotifers consists of the trophi and a gut. When prey is captured, it's first processed in a modified pharynx known as mastax. Also known as trophi, it's lined by chitinous material and looks like a translucent jaw. In the trophi, food material may be pierced or ground before being passed to the stomach through the esophagus.

For some of the species (e.g. members of the family Collothecidae), part of this structure is modified to form the proventriculus which acts as a food-storage organ. For the majority of species, food is digested in the stomach before being excreted through the anus.

For some of the species, e.g. members of genera Asplancha and Asplanchnopus, the gut ends in a blind stomach. As a result, waste material is excreted through the trophi.

* The trophi of given species are pigmented.

Muscular System

The muscular system of Rotifers consists of longitudinal and circular muscles that serve several functions. Through muscle contraction in loricate species, pressure in the pseudocoel is increased causing it to act as a hydrostatic skeleton.

These muscles also serve to retract the corona in some species resulting in various outcomes (e.g. in Brachionus calyciflorus, this action causes flaccid articulation between spines and lorica to become stiff and swing outwards which deters predators).

Some of the other functions of this muscle system include:

- Retracting the foot

- Controlling movement of arm-like appendages

Neural System

For members of the phylum Rotifera, the neural system/nervous system simply consists of a cerebral ganglion and a few ganglia. The cerebral ganglion (brain) is dorsally placed on the mastax with some ganglia also being found in the foot or the organisms (for those possessing a foot).

Apart from the cerebral ganglion, Rotifers have also been shown to possess a few sensory organs that serve to detect changes in pressure, light, or chemical compounds. Therefore, some of these organs include photoreceptors, mechanoreceptors as well as chemoreceptors. Mechanoreceptors (located in Mechanoreceptive bristles) and chemoreceptors (Chemoreceptive pores) are located at the corona.

Photoreceptors, on the other hand, are present in the eyespots in some of the species (these eyespots may be lost in some species when the organism attaches to a substrate). In these locations, these receptors contribute to feeding and movement given that they allow Rotifers to not only sense the presence of prey/predator as well as any other changes in their environment. In the process, they may move towards favorable areas (with food, etc) or away from predators, etc.

Reproductive System

Although different sexes (male and female) exist, studies have shown male Rotifers to be very few in some species with a short life span. Female Rotifers are very common and may contain one or more gonads depending on the species. Whereas members of the class Monogononta have a single gonad, those of the class Digonota have a pair of gonads.

Generally, their reproductive system consists of three parts that include:

- Ovary - small in size with a syncytial mass that is associated with the vitellarium

- Vitellarium - Syncytial with a constant number of nuclei

- Follicular layer - Covers the other two parts and forms the oviduct in some of the species

* Depending on the species, male Rotifers may be significantly smaller in size when compared to the female.

* The majority of Rotifers are oviparous (eggs are released out of the body where they develop).

Based on gonad arrangement, Rotifers are divided into two major groups that include:

· Monogononta - Rotifers with a single gonad that is medially located. They may be gonochoric (where the male is significantly small) or parthenogenetic (requiring no male for fertilization).

· Bdelloidea - These Rotifers possess two gonads that are bilaterally arranged and tend to be parthenogenetic.

Ecology

The majority of free-living Rotifers can be found in aquatic environments. However, they can also be found in terrestrial habitats with some water or high moisture.

For moss-dwelling Rotifers, which can be described as terrestrial Rotifers, Bryophytes provide the water space that allows Rotifers to survive. Rotifers found in such habitats (terrestrial and wetlands) move by crawling on leaves and branch surfaces covered by a film of water. Here, they feed on bacterial and small protozoa.

Rotifer Adaptations

Members of the phylum Rotifera can be found in different environments and habitats across the globe. While some of the species prefer given environmental conditions, the majority have been shown to be euryoecious and thus capable of surviving in a range of conditions.

Some of the adaptations that contribute to their bryophyte living includes:

· Are particle feeders and can survive on algae and detrital matter

· Have a long spine for attachment purposes. In water environments, these spines have been shown to serve as floating devices

· Some of the species are very small in size which allows them to hide from predators in bryophyte

· Small Rotifers use cilia to move around quickly

· Some of the species (e.g. Habrotrocha species) secrete substances (mucus) that allow them to appear larger than they really are and thus deter predators

Reproduction

Depending on the species, Rotifers have a lifespan of between 30 and 40 days. However, some of the species are suspected to have a significantly shorter lifespan (a few weeks). The mode of reproduction is largely dependent on the species given that there are different forms of Rotifers.

Whereas male and female forms are present in some species, allowing for sexual reproduction, only female forms are present in other species. For this reason, some species rely on asexual reproduction as a means of multiplication while others can reproduce sexually.

Reproduction in Rotifers may involve the following methods:

Cyclical Parthenogenesis

This mode of reproduction is common among monogononts and does not require male forms. Here, females (amictic females) produce subitaneous eggs which are diploid. Depending on the species, eggs may be produced at any given time of the year. These eggs undergo mitotic division to produce females as the cycle continues.

In some cases, male forms are produced which allows sexual reproduction to take place. However, this also requires that females produce both mictic females that are capable of sexual reproduction.

It's worth noting that amictic females continue to be produced and the proportion of each group (mictic and amictic daughter) is largely dependent on the type of strength of mictic stimulus (temperature, chemicals, etc).

When male Rotifers and mictic females are produced, mating allows female eggs to be fertilized in order to form an embryo. In the event that the female eggs (haploid eggs produced through meiosis) are not fertilized, they develop to produce haploid males.

Fertilized eggs, on the other hand, are diploid and develop to produce cysts (resting eggs). Due to the thick walls surrounding them, these eggs are able to survive harsh environmental conditions. Under favorable environmental conditions, the eggs hatch and give rise to amictic females capable of reproducing asexually.

Amphoteric Reproduction

This type of reproduction has been identified in the life cycle of monogonont organisms including members of the genera Sinantherina, Asplanchna, and Conochilus. Here, females are amphoteric and thus capable of producing both male (through haploid eggs) and female (through diploid eggs) forms.

Some of the species have been shown to produce diapausing embryos (resting eggs/cysts) and females or resting eggs and males.

Parasitic Rotifers

For the most part, Rotifers are free-living organisms that can be found in various aquatic and terrestrial environments. However, a few species have been shown to be parasites of sponges, fish, crustaceans, algae as well as other rotifers. By attaching to these hosts, Rotifers are able to obtain the nutrients they require for survival.

Some of the most common parasitic species include members of Seisonidae, Monogononta, and Bdelloidea. While some of the species live as commensals and do not cause harm, others have been shown to cause harm to their hosts. Currently, no parasitic Rotifer has been shown to affect human beings.

* Rotifers are themselves hosts to such parasites as Microsporidium. These parasites have been shown to help control the population of Rotifers in various environments.

Culture of Rotifers

Some of the culture methods that may be used to culture Rotifer include:

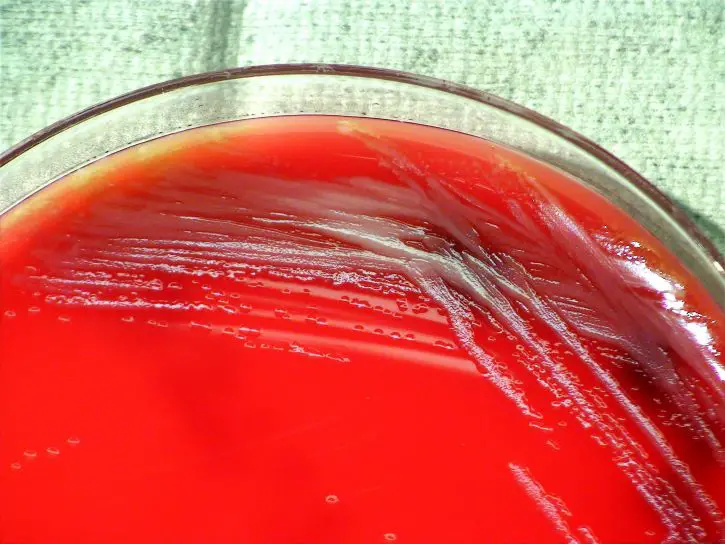

Batch Culture

This involves inoculating algae (at exponential growth phase) with freshwater Rotifers at between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius and 8.0 pH. Phytoplankton may then be added or any other appropriate food substitute. To prevent chances of a crash, 10 to 20 Rotifers per milliliter are then added.

Continuous Culture

This involves using a larger container. Here, Rotifers are introduced into a container at the rate of 10 to 20 Rotifers per milliliter. This is followed by adding phytoplanktons into the container. As the Rotifers multiply in numbers, a portion of the population is removed daily in order to avoid overpopulation and subsequent pollution.

The continuous culture technique may also be carried out with the use of excess food. Here, excess foods (and faeces) are fermented in a bucket for about 2 weeks. This is then used to produce algae that are in turn fed to Rotifers as recycled nutrients.

Return to phylum Aschelminthes

What does Phylum mean in Biology?

Also interesting: Tardigrades - Classification, Reproduction, Habitat and Survival

Return from learning about Rotifers to MicroscopeMaster home

References

Glime, J. M. 2017. Invertebrates: Rotifers. Chapt. 4-5.

Linda May. (1989). Epizoic and parasitic rotifers.

Oliver Galvez Castro. (2006). Culture of the freshwater rotifer, Brachionus calyciflorus, and its application in fish larviculture technology.

Robert Lee Wallace and Terry W. Snell. (2010). Rotifera.

Links

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/rotifera

Find out how to advertise on MicroscopeMaster!