Phylum Aschelminthes

** Examples and Characteristics

Overview

The phylum Aschelminthes is an obsolete group that comprised pseudocoelomate, triploblastic organisms with bilateral symmetry.

Members of the phylum have an elongated body with a circular cross-section and are thus referred to as roundworms in some literature.

They are widely distributed and can be found in various habitats (in aquatic and terrestrial environments) as free-living organisms or as parasites of plants and animals.

Before it was abandoned and members of the group divided into separate phyla, Aschelminthes consisted of five main classes including:

- Rotifera

- Gastrotricha

- Kinorhyncha

- Nematoda

- Nematomorpha

Examples and Characteristics of Aschelminthes

* Before looking at some examples of the phylum Aschelminthes, it is worth noting that the phylum no longer exists and most of the Class divisions are now distinct phyla.

Rotifera

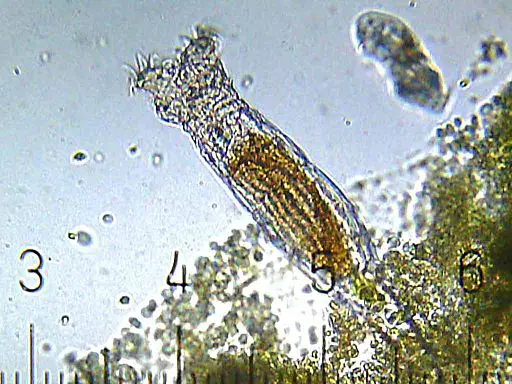

The class Rotifera consists of over 2,000 species commonly found in freshwater habitats. A few species can also be found in brackish and marine habitats as well as thin films of moisture.

They are generally small in size, ranging from 50 to 2000 um in length. Because of their small size, they are easily mistaken for protists (eukaryotic organisms that are neither plants nor animals). Unlike protists, however, rotifers are metazoans which means that they are multicellular organisms whose cells have differentiated into tissues and organs.

Though members of the group exhibit significant morphological variations allowing them to adapt to their respective habitats, they share several important characteristics.

For instance, most of the species have an elongated body with three distinguishable parts; the head, trunk, and foot.

In bdelloid rotifers, the head section (at the anterior portion of the body) consists of a mouth, corona (ciliated), cerebral ganglion, and a mastax. The stomach, intestine, and pseudocoel are found in the trunk while the foot region possesses two toes.

Ciliated species, particularly planktonic forms, use cilia for feeding and locomotion. The majority of species, however, are sessile and can be found at the shores (littoral substrata).

Some of the other characteristics associated with rotifers include:

Lorica - In some of the species, the cuticle is thick and rigid. As such, it's known as lorica. The head region of the organism may retreat into the lorica.

Foot - The foot region is post-anally situated and contains cement glands. These are small, mucus-secreting organs that help anchor the organism to a substrate.

Digestive system - Rotifers have a complete digestive tract.

Parts of the digestive tract include the mouth, mastix, esophagus, salivary and gastric glands, the stomach, intestine, cloaca etc.

Once food material is ingested through the mouth, it's sieved and disrupted by jaw-like, horn-like pieces known as mastax in the pharynx. Digestive enzymes are produced by the two glands (salivary and gastric glands) to promote digestion in the stomach before the absorption of nutrients in the intestine. Lastly, waste materials are excreted through the anal opening.

The majority of rotifers are nonpredatory and feed on a variety of organic materials in their surroundings. Using cilia, they can draw particulate organic material (plant and animal material) to feed on. Others, like asplanchna, are predators and mostly prey upon protozoa.

Musculature - They possess longitudinal and transverse muscle.

Nervous system and sensory organs - The nervous system of rotifers consists of three ganglia (the cerebral ganglion, mastax ganglion, and pedal ganglion) and a series of nerves. Sensory organs include one or two pairs of antennae and eyespots.

Reproduction and life cycle - Although they can reproduce asexually (parthenogenetically), rotifers usually reproduce sexually.

They are dioecious meaning that there are male and female individuals. Males, however, are generally fewer, smaller in size, and have a shorter life span. An hour after hatching, they can detect and find females using sensory receptors. Mating involves the attachment of the penile organ to the coronal region of the female for internal fertilization.

The eggs then hatch into a young rotifer that matures within a short period of time. Here, however, it's worth noting that eggs (amictic) can be produced and hatch without mating. This is known as parthenogenesis. Some of the species can survive harsh environmental conditions (e.g. desiccation) by forming cysts.

Some examples of rotifers include:

- Collotheca species (Collotheca ornata, Collotheca balatonica)

- Brachionus species (e.g. Brachionus calyciflorus)

- Philodina species (e.g. Philodina acuticornis)

- Asplanchna species (Asplanchna priodonta)

Gastrotricha

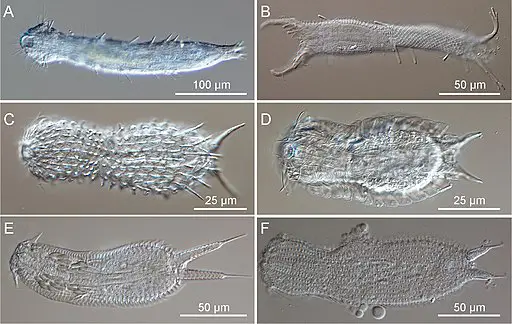

The class Gastrotricha consists of about 800 species.

Like Rotifera, gastrotrichs (Gastrotricha) are microscopic invertebrates (between 0.1 to 1.5 mm in length) found in marine and freshwater environments throughout the globe. Most of the species are colorless with a ventrally flattened, spindle, or tenpin-shaped body.

The body consists of two distinguishable parts; the head and the trunk. Some of the structures located on and in the head region include sensory cilia, a spiny cuticle, mouth, and pharynx as well as the brain. The trunk, on the other hand, contains the digestive tract, reproductive organs, salivary gland, surface spines, and bristles. The posterior portion of most species (post-anal) is also forked and may contain adhesive glands.

In freshwater, gastrotrichs are mostly found on sediments and vegetation. Some members of the families Dasydytidae and Neogosseidae are good swimmers and can be found in shallow lakes. Many species can also be found in anaerobic environments where they can survive for months with very little oxygen.

Other characteristics associated with gastrotricha include:

The lack of body cavity - The interior part of the body is filled with mesenchyme. For this reason, they do not have a body cavity commonly found in many other animals.

Complete digestive system - They have a complete digestive system consisting of the mouth (surrounded by short bristles in some species), buccal capsule, the pharynx, and a y-shaped lumen.

The undifferentiated gut eventually connects with the anus. Gastrotrichs feed on a variety of organisms including algae, protozoa, and bacteria. However, they can also obtain nutrients from detritus.

Respiratory and circulatory system - Like a number of other invertebrates, gastrotrichs do not have a respiratory and circulatory system. Gas exchange, therefore, occurs through simple diffusion where oxygen diffuses directly into the cells.

Nervous system and sensory organs- The nervous system of gastrotrichs consist of a brain and lateral nerve cords.

The brain (a pair of ganglia) is located near the pharynx in the anterior portion of the body. The pair of lateral nerves extend the entire length of the body. Eyespots, bristles, and cilia are the main primary organs.

Whereas eyespots are present in a few species (detect changes in light intensity), bristles and cilia (mechanoreceptors) can be found in most gastrotrichs.

Reproduction - All gastrotrichs are hermaphrodites. However, cross-fertilization is the most common form of sexual reproduction.

Following fertilization (internal), the eggs are released into the environment through the body wall. Under favorable conditions, the juveniles mature only a few days after hatching (no larval stage).

Although sexual reproduction occurs, studies have shown most freshwater gastrotrichs to be parthenogenetic. In this case, fertilization is not necessary for the spontaneous development of the embryo. In some cases, particularly under poor conditions, thick-walled eggs are produced. These eggs are mostly dormant and can survive for several years.

Some examples of Gastrotricha species include:

- Chaetonotus species (e.g. Chaetonotus testiculophorus and Chaetonotus maximus)

- Lepidodermella species (e.g. Lepidodermella squamata)

- Macrodasys species (e.g. Macrodasys caudatus and Macrodasys imbricatus)

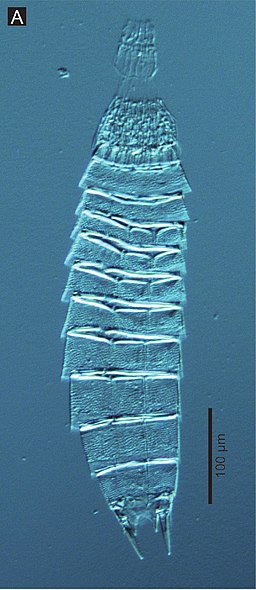

Kinorhyncha

Kinorhyncha contains over 200 species commonly found in marine sand and mud. In marine and brackish water, they can be found at various depths from 8 to about 8,000 meters. Some of the other habitats they are likely to be found in include oxygenated sediment layers associated with organisms like sponges, algae, and ectoprocts.

Like Gastrotricha and Rotifera, Kinorhynchs are microscopic animals ranging between 0.13 and 1.04 mm in length. Most of the species are yellowish-brown in color and segmented (13 or 14 superficial segments known as somites).

The head, which is the first segment, consists of a retractable oral cone, oral stylets (surrounding the oral cone), a mouth, scalids, and a brain. Generally, there are about 9 outer stylets surrounding the oral cone and 3 to 4 rings of inner stylets. Moreover, each of the rings consists of about 5 stylets.

Scalid rings (5 to 7 rings) are located behind the oral cone. Each of the rings consists of 10 to 20 circles depending on the species and each circle has between 54 and 93 scalids.

The neck region is located behind the head segment. The neck contains about 16 placids in which the head can be retracted.

The rest of the segments (zonites) make up the trunk and are covered by an exoskeleton made up of chitin and a membrane-like spicuticle. Some of the organs and structures found in the trunk region include the esophagus, reproductive organs, the ventral nerve cord, as well as gonopore.

Some of the other characteristics of Kinorhyncha species include:

Epidermis - The epidermis is located beneath the tergal and sternal plates. It's in close contact with the nervous system and non-ciliated.

Locomotion - Kinorhynchs use anterior scalids for movement. By retracting and extending the head using these structures, they can also burrow through mud and sand.

The digestive system and feeding - Like their counterparts, Kinorhyncha species also have a complete digestive system.

From the mouth, food material moves to the buccal cavity and then to the sucking pharynx. From the pharynx, they are moved to the esophagus (lined with cuticle) and then to the gut (mid and hindgut) which consists of epithelial cells. The anus is located in the last segment.

Depending on the habitat, Kinorhynchs feed on a variety of materials including organic material, algae, as well as bacteria, and diatoms.

Nervous system and sensory organs - Kinorhynchs have a simple nervous system that consists of ten ganglia around the pharynx. This simple brain is divided into several segments including the anterior somata, neuropil somata, as well as the posterior somata.

In addition to the ganglia, the nervous system also comprises longitudinal nerves. These nerves run longitudinally into the trunk and are connected to each other by a pair of commissures in each segment. Sensory organs include microvillar eyespots and the ocelli located behind the mouth cone.

Reproduction - Kinorhynchs are dioecious which means that there are two separate sexes. Some of the reproductive organs and structures in male forms include 2 or 3 spicules and gonopores. Females have gonads (with germ and nutritive cells) and oviducts.

During copulation, the spermatophore is transferred to the female for internal fertilization. Fertilized eggs are then released into the environment and attached to various surfaces. Hatching produces a juvenile with a head, scalids, neck, and trunk segments. It then goes through six main stages of development (involving molting) before reaching maturity.

Some examples of Kinorhynchs include:

- P. communis

- Echinoderes aquilonius

- P. kielensis

- P. flaveolatus

Nematoda

The class Nematoda consists of animals commonly known as roundworms. There are over 25,000 species in the group found in both terrestrial and aquatic environments.

Like most animals, they are triploblastic organisms with bilateral symmetry. They are also slightly bigger than some of the other Aschelminthes, ranging between 0.2 mm to 11.0 mm in length and 0.01 to about 0.05 mm in width. They are also Pseudocoelomate, unsegmented, and mostly colorless.

Although they are not segmented, several organs and structures can be identified including the mouth region, stylet and stylet knobs, the median bulb, esophagus, intestine, and the anal pore.

Like some of the other Aschelminthes, they also have a simple fluid-filled cavity known as the pseudocoelom. The body wall consists of a syncytial epidermis (without cilia) as well as a flexible cuticle made up of collagen. This serves to protect the animal from abrasion (as a result of friction with soil and other surfaces) and also protects parasitic forms from host enzymes.

Free-living species can be found in different types of habitats where they exist as saprophytes. Parasites, on the other hand, can be found in a number of hosts including human beings and other animals. There are also predatory and phytophagous species that feed on smaller animals and algae respectively.

Some of the other characteristics of nematodes include:

Locomotion - They use longitudinal muscle for movement. Their movement resembles that of snakes (a whip-like movement).

Digestive system - Nematodes also have a complete digestive tract which consists of a mouth (surrounded by three lip-like structures), a stylet (retractable), and a muscular pharynx (capable of sucking in food material), a long intestine, and an anal opening located at the posterior end.

Nervous system - The nervous system consists of ganglia located around the pharynx as well as dorsal and ventral nerve cords. Chemoreceptors are the most common sensory organs. They might be located in the head or posterior region (the tail end).

Reproduction - The majority of nematodes are dioecious and thus exhibit sexual dimorphism.

Internal fertilization is followed by the release of numerous eggs (more than 100,000 eggs a day). These eggs are multilayered with a smooth or rough surface and capable of surviving harsh environmental conditions. Once they are hatched, the juvenile forms go through four stages of development (no larval stage) to reach maturity.

Infections - In human beings, nematodes are responsible for several infections including ascariasis, Enterobiasis, and filariasis among several others.

Examples of Nematode species include:

- Trichuris trichiura

- Enterobius vermicularis

- Ancylostoma duodenale

- Ascaris lumbricoides

- Meloidogyne incognita

Nematomorpha

The class Nematomorpha consists of over 300 species commonly found in freshwater habitats.

Also known as Gordian worms, nematomorphs are characterized by a long and slender body. They are also larger than the other Aschelminthes, ranging from 50 to 100 mm in length and 1 to 3mm in diameter. However, some can grow to be over 1 meter in length.

Adult forms are characterized by a thick cuticle that consists of the inner, lamellate, fibrous layer, and outer homogeneous layer. They are also generally darker in color (black in color and lack cilia). Some of the species have a blastocyst cavity (blastocoelom) but in others, the space is filled with mesenchyme.

Some of the other characteristics associated with Nematomorphans include:

- Areoles on the outer layer - The areoles may have an apical spine in some species

- Thick longitudinal muscles

- Natatory bristles that help in swimming

- Respiratory and circulatory systems are absent

Nervous system - The nervous system of nematomorphans consists of a circumpharyngeal cerebral ganglion (located in the calotte) as well as a pair (single in some species) of ventral nerve cords. Sensory organs may include cuticular areoles which are sensitive to touch and pressure. They are also suspected of acting like chemoreceptors.

Digestive system - Generally, the digestive system is mostly complete in larval forms. However, it begins to degenerate as the organism develops into adulthood. For this reason, adults do not eat. Rather, they may absorb nutrients through the epidermis in water.

As compared to adults, larval forms exist as parasites and obtain nutrition from the body tissues of the host. They may feed on the tissue or absorb nutrients through the epidermis.

Reproduction - Nematomorphans are dioecious animals. However, the male forms lack penile spicules (they have one or two testes). During mating, males wrap themselves around the body of the female in order to deposit sperm near the cloacal pore of the female.

Once the sperm enters the cloaca, the eggs are fertilized in the seminal receptacle before being released into the environment. Though most of the species reproduce sexually, studies have shown that the species Paragordius obami is parthenogenetic.

* Some hosts of parasitic nematomorphans include insects like crickets and grasshoppers. Frogs and fish act as definitive hosts of adult forms.

Some examples of Nematomorphans include:

- Paragordius varius

- Chordodes japonensis

- Gordius aquaticus

- Chordodes mizoramensis

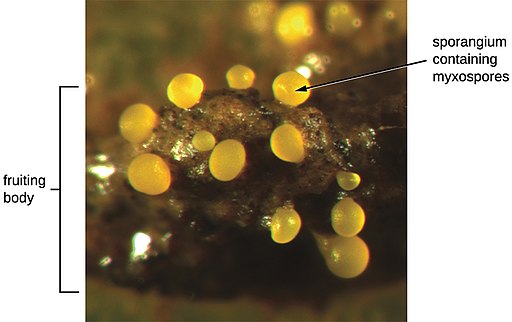

* Some of the other members of the Phylum Aschelminthes include Gnathostomulida and Acanthocephala. Gnathostomulids (jaw worms) are microscopic Aschelminthes commonly found in marine environments (particularly in sand and mud).

Acanthocephala (Acanthocephalans) are also known as spiny-headed worms. They are characterized by a spiny eversible proboscis and exist as parasites of fish, birds, mammals, and invertebrates.

What does Phylum mean in Biology?

Return from Phylum Aschelminthes –Examples and Characteristics to MicroscopeMaster home

References

Strayer, D., Hummon, W., and Hochberg, R. (2010). Gastrotricha. https://www.caryinstitute.org/sites/default/files/public/reprints/thorp_covich_gastrotrichs_2010.pdf

Musto

e, G. (2014). Aschelminthes. Beaches and Coastal Geology.

Neuhaus, B. and Higgins, R. (2002). Ultrastructure, Biology, and Phylogenetic Relationships of Kinorhyncha. Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 42, Issue 3.

Links

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/rotifera

https://www.britannica.com/animal/aschelminth

Find out how to advertise on MicroscopeMaster!